Bettina Drummond

Bettina Drummond is highly regarded in both the United States and Europe. She teaches the French Classical method of dressage, along with some of the principles of Baucher when appropriate for the horse’s development. She is a practicing Baucheriste trainer, following the tradition of the Portuguese Master Nuno Oliveira, who achieved his phenomenal results by grafting the principles of Baucher onto a classical foundation.

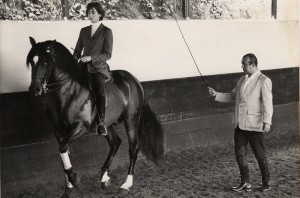

Bettina spent 17 years in training with Master Oliveira, beginning at age seven. She earned the coveted spurs awarded to instructors at 17, and was recognized as a master trainer at 21. She was also influenced and coached by some of Europe’s finest trainers, including General Durand, Ecuyer en Chef and Commandant of the French National Equestrian School in Samur, and Lieutenant Colonel Paolo Angioni of the Italian Cavalry. Based in Washington, CT, Ms. Drummond travels across the U.S. and to France to teach and train. She can occasionally be found performing exhibitions with fabulous horses, many of which are her own Lusita

In 2012, Bettina’s artistry on horseback earned her the prestigious Action Maverick Award from STREB in Brooklyn, N.Y. During the award ceremony, she performed for banquet attendees on the Lusitano stallion Que Macho. You can see Bettina’s ride at STREB by clicking here.

Bettina Drummond: The Artist as Rider

By Lynndee Kemmet

Published 08 May 2008 by DressageDaily, www.dressagedaily.com.

While much of the dressage world seems in conflict over the question of whether dressage is art or sport, classical trainer and rider Bettina Drummond faces no such conflict. For her, riding has always been art.

While much of the dressage world seems in conflict over the question of whether dressage is art or sport, classical trainer and rider Bettina Drummond faces no such conflict. For her, riding has always been art.

Drummond was a budding pianist at the age of seven when her mother, Phyllis Field, pulled her from her studies in Paris and sent her off to Portugal to study with the great riding master, Nuno Oliveira. For the next 20 years, Drummond was immersed in the classical system of riding, most particularly the French training method. Her childhood and early adult years were spent in the company of some of the world’s leading academic equestrian of the last half of the 20th century, many now long gone, but very much alive in Drummond’s memory. The knowledge she gleaned from these masters, both as a student and through eavesdropped conversations among them, have carried with her through her life and is reflected in her own riding and training.

While some might use that knowledge to gain a competitive edge, Drummond has long sought to use it to develop herself as an artist. Training has been the process by which she has carefully developed her equine artistic partners so that together, they create art. It pleases Drummond most when those watch her ride are as moved by it as they are when viewing a phenomenal piece of artwork or listening to the performance of a world-class musician. Indeed, while others might define her as a rider and trainer of horses, she defines herself as an artist. It’s for that reason that Drummond has preferred to display her riding in exhibitions, often for charity causes, rather than in the show ring.

“Art is the overlap of words, sounds and feelings. The key of art is not getting lost in it,” she said. “For centuries, artists have recognized the horse as a work of art in itself. As a rider, my goal is to allow the horse to express its own artistic nature.” The recognition that riding is in itself a form of art came early to Drummond and it was Oliveira who inspired that recognition. When she was 10 years old, she sat one day reading a book (A Collection of Lectures on Literature by Nabokov). As she was reading a passage where the words evoked the idea of lightness and form, she glanced up and caught sight of Oliveira on horseback silhouetted by the sun. It was at a moment when he and the horse were in perfect balance.

“What struck me was how immobile was his body and how in balance he was with the horse. The vision fit the force of the words,” Drummond said.

Born with a Love of Art and Horses

Born in London, Drummond, 45, is a member of the Marshall Field family on her mother’s side and of ancient Scottish royal blood on the side of her father, Bend’or Drummond. She was raised mostly in Europe, particularly Paris, but spent much time in America as her mother wanted to ensure she had American citizenship. It was always her mother’s plan that she be educated in the classical system of riding – as often practiced in the Latin or French systems – so that she could one day return to America and instruct American riders in that system. Drummond’s own education as a rider began at the tender age of three on a family estate in South Carolina.

“My first memory of riding was being in a Western saddle that was way too big for me. My feet stuck out on each side of the pommel,” she said. That pony ride was the first step in Drummond’s life-long equestrian education. Riding, however, was not her first love as a child. “I’m a thwarted musician. I always wanted to be a pianist.” And indeed, Drummond still studies classical piano. She shares this musical interest with her mentor, for Oliveira was known for his passion for opera. It was only as time went on that she realized riding could become a way through which she could express her artistic nature.

Her other artistic love is poetry and her poetry has circulated through Europe and been well-received among a closed circle of distinguished European poets.Among poets, she credits Baudelaire and the Russian Anna Akhmatova as her greatest influences. Early in her riding education, she discovered that riding and poetry are symbiotic. Just as that vision of Oliveira so aptly fit the words she was reading that day when she was 10, Drummond has since sought to match vision to words, often matching photos of horses with her poetry.

Oliveira taught her that the opportunities to express art through riding are endless because each horse is an individual. This is why training must be tailored specifically for each horse. But Drummond has understood that this individuality in horses also means that every horse provides her with a new opportunity to hone her craft and present her art in a new way.

“As a rider, what I wish to pursue with each of my horses is to find that point of balance. And my development as a trainer and rider has allowed me to find that point much quicker with each succeeding horse. I am grateful that Oliveira taught me early on in life how to feel this moment,” she said.

The movement she saw Oliveira ride silhouetted against the light was a transition from walk to piaffe. When she reached that point in her own riding where she experienced that movement in perfect balance for herself, Drummond came to understand that as a rider, one can tap into how horses speak to us through their bodies. “The horses themselves are the art and we simply insert ourselves into that.” It was a process through which Drummond has passed often in her life as a rider – first seeing it and then experiencing it.

Bettina Drummond’s Art Inspires Other Artists

As an artist, Bettina Drummond measures her success by the feelings her riding evokes in others and other artists in particular have always been attracted to her, both for the inspiration her riding gives them as artists and as fellow riders.

“A work of art always insinuates the soul of the artist who created it. I recognized instantly in Bettina someone who could educate me in the art of riding. Owning horses and not being the sportive type, a door had opened! I was stunned one day as I watcher her ride when I learned the horse she was riding that day had only recently arrived at her barn. Watching the ride I wondered, would horses respond to an artistic touch?,” asked Gerald Incandela, a renowned photographer whose work hangs in galleries around the world. “The knowledge of one art form is a useful tool to understand another art form. Perhaps because all art forms have in common a good composition, balance, rhythm or underlying ‘drawing,’ whether music, architecture, painting, dance or riding.”

Two years ago, actor and author Tab Hunter had an opportunity to witness Drummond’s riding when Incandela invited him to watch her ride one of his Lusitano stallions. Hunter, perhaps best known as a movie actor, has himself been involved with horses since the age of 12.

“The first thought that came to my mind when I saw her ride was, what a ‘sympathetic rider’ she is. I first heard the expression, ‘sympathetic rider’ many years ago in Spain while riding at the Club de Campo. “Paco” Goyoaga’s wife, Paula, used the phrase and I have never forgotten it. Riding is an art, no matter what the discipline, and with dedication the ‘sympathetic rider’ takes the art of riding to the next step. Bettina creates magic,” Hunter said.

Any work of art, Drummond said, should not only move people but also serve as a catalyst that inspires more art. Her riding has certainly done that. The image of her on horseback has inspired other artists, who have used that image to create their own art. For example, Incandela has created a number of pieces of art from watching Drummond ride.

“The first time I saw Bettina, she was on a horse. I saw a beautiful ‘drawing’ in the sense that the lines of her body and the horse she was riding were fluidly and graciously linked. My eye could travel on these two bodies as if it was one. The result was a picture of balance, harmony and peace. Beauty is the word that comes to mind, and a beauty that is internal as well since it must have involved a psychic connection between horse and rider,” Incandela said.

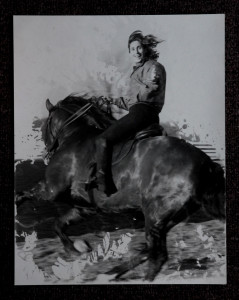

One image in particular, of Drummond in a moment of complete joy while riding Boccanegra, an Andalusian stallion owned by her sister, Fiona Drummond, has become a widely-regarded piece of photographic art. In describing the photo, Incandela said he sought to capture “a very happy moment when there was such a beautiful combination of power and joy.”

Bettina Drummond Brings Art to Riding and Riding to Artists

Since she defines herself as an artist, Drummond is happy that other artists gravitate to her. It is, in a sense, affirmation for her that her way of expressing art – through riding – has gained acceptance among other artists. For other artists who also ride, Drummond has opened doors by showing them that there is a way for them to take their art into their riding.

“My love for horses, once driven by competitive riding, always had a flame that was fanned by images of old. Ancient memories arise when I watch sensitive yet powerful riding with the purest intentions of becoming one with the horse, and that was my first impression of Bettina’s riding. Quite simply put, I now find that the silhouette of a classic Iberian horse and rider seems to transport me; time can stand still and admired old engravings come alive before my eyes,” said Mari Austad-Bourque, a successful photographer and also rider. “Bettina has opened my eyes to a new level of possibilities in the horse and rider relationship, when the simplest of movements can become art and music is made in the silence of the arena.”

As with Incandela, Austad-Bourque was so inspired as an artist by what she has seen in Drummond’s riding that she also sought to capture moments of it on film, and did so – beautifully. She created a series of three photos of Drummond with her Lusitano stallion Ilyad that has now been made into a beautiful black and white poster.

“I was fortunate enough to capture a moment between Ilyad and Bettina when they were surrounded in sunlight in an otherwise dark space, both seemingly in deep meditation, both mutually passionate and mutually respectful,” Austad-Bourque said.

For Drummond, the question of whether dressage is art or sport results from the inability of dressage to find the balance between the physical development of the body of both horse and rider – which makes it a sport – and the tempering of the mind of both partners through the medium itself, which is required in any art form. When she speaks of her own form of riding, Drummond refers to it as a craft and she sees her life as devoted to the “craft” of riding. As with all craftsmanship, she believes that being truly devoted requires knowledge of that craft from its beginning to the present time. This is why Drummond incorporates into her training and riding, movements and techniques passed down through generations that others might consider archaic and useless for modern riders.

“The craft is the link between art and sport. If the craft dies, that balance dies as well,” she said. “Good sport riders don’t forget the feel and good artistic riders don’t forget the technique.”

Balance is central to all aspects of Drummond’s life. And to understand that, is to understand her. It also explains her deep respect for the spirituality of Buddhism and the Dalai Lama in particular, who, she says, is the best modern example of seeking balance in life and the middle way. Drummond, rather seriously, says that were the Dalai Lama ever to need a standard bearer, she would immediately apply for the job. “It’s why I continue to practice riding all the movements with only one hand, so the other would be free to carry his standard should the day come when that post would be open, I will be the first to apply for the job!”

Artistic Riding Merges the Physical with Feel and Thought

Riding is perhaps one of the most complex forms of art because it requires the merger of three things – physical use of the body to mold the content, feel to shape it and thoughtfulness to create the form to hold that content. While most riders can understand that physical fitness, balance and body control will make them better riders, the role of feel and thought are less understood. Yet, Drummond believes these two are inseparable.

“If one thinks, one must feel. To think is to translate to specific feel and to feel is bound to lead to more exciting and precise thought,” she said. Her ambition as an artist is to allow a seamless transition. “All our thinking and training has to do with preparation. Horses allow it to happen. What fascinates me with horses is the moment and apex of balance. The moment there is balance, all things are possible. The moment you lose it, nothing can be done, even with force and skill. It’s much the same with words. You create a balance and through it, you allow people to feel how to live on and through that expression.”

Drummond herself is not only a “thoughtful” rider, but a thinker, period. Renaissance woman is a term that aptly applies to her. She has a degree in philosophy and attended the University of Chicago in order to study with Alan Bloom, a noted philosopher. She speaks five languages – French, English, Portuguese, Spanish, Russian and Latin. And when it comes to music, she’s a walking musical encyclopedia. While she can rattle off details of particular classical pieces and their composers, she lists Tom Petty and Donovan as two musicians who have inspired her for the way they have approached their art. She can hold her own in conversation with anyone on topics ranging from wine to great authors to world politics.

“As a rider, I believe you must be a thinker. You get off, go home and think. That’s the study of philosophy – cause and effect,” Drummond said. She recalls with humor having once been told that Oliveira was heard to say to a friend, “You know, Bettina, she’s even intelligent.” Drummond’s mother shared this interest in intellectual pursuits, particularly philosophy. Hugo Vidal was one of her teachers.

Bettina Drummond’s Latest Role – Teacher

Teacher is a role that Drummond herself is taking on more and more in her life because she believes that “it’s important that the craft of classical riding grow and not die. And it would seem a shame to me if I did not pass on what I’ve learned.” She admits, however, that learning to be a teacher was a very long process for her. Because she is an instinctive rider, she lacked the patience required of a good teacher. It was only through years of working with good teachers that she learned how to teach and gained the patience needed to explain things to students. Drummond takes the role of teacher very seriously and is quick to distinguish between a “riding instructor” and a “teacher.”

“We need ways to reward the craft of teaching, not just reward who wins in shows. When I made mistakes in my training, I had intellectuals in the art of training with whom I could converse and seek advice to correct my mistakes. People who are steeped in theory seem to be in shorter supply today.”

When asked to identify those who have been there to guide her own formation as a rider, Drummond credits not only her mentor, Oliveira, but others of his generation. “Oliveira taught me how to feel and know when it’s right. Gen. Durand made me consider the responsibility of caring for young horses and taught me to have no ego.”

These European masters may have formed Drummond as a child and young adult, but she credits Dr. Max Gahwyler, a member of the U.S. Dressage Federation Hall of Fame and author of the Competitive Edge series of books with giving her the courage in her adult years to find the artistic rider within herself. It was Gahwyler, Drummond said, who “helped me find a necessary skill to learn again as an adult rider.”

Oliveira was a genius on horseback, but he was also a taskmaster who demanded perfection in his students, which caused Drummond “to develop a fear of being less than perfect and to have a foolish notion that one should, with ability, aptitude and training, be instantly able to perform.” As an adult rider, it was Gahwyler who taught her that when experimenting with one’s riding, “ballpark” was good enough as a starting point. Drummond admits that she and Gahwyler may seem an unlikely pair to have formed such a long and close friendship.

“Max was so genuinely curious to help me understand his world and also aprreciative of what I already knew that he made learning fun for me again. It was amusing really, since in my twenties he and I had held opposing views, especially in regards to the use of Baucherism. It was the fact that he and I could exchange our profound interest in the evolution of training and its history, as well as our common delight in the antics of young horses, that told me that what we both had watched and learned – he from schools in Vienna and Geneva and I from schools in Paris and Lisbon – was not obsolete and anachronistic.”

In more recent years she has sought coaching support from FEI “O” judge Bernard Maurel of France. She had met him as a teenager when she was training with Oliveira. Maurel has, she said, “been gracious enough to be an eye on the ground for me and I trust his eye because I know that he understands Lusitanos.” Maurel has helped Drummond understand how to take the classical, artist approach that formed her and apply it to the competition arena – something she must frequently do when rehabilitating show horses, such as when she returned to the FEI ring the Lusitano stallion Quarteto do Top.

As a teacher herself, Drummond’s style reflects her approach as a rider and trainer – waiting for the moment. “As a teacher, I’m happy to wait for students to make their own decision of what is right for them. I don’t feel the need to push. All horses and riders have a story to tell, and I love listening to the stories. At times I might say, ‘You need more punctuation,’” Drummond said.

The students Drummond most likes are those who come to her because they “want to hear their horses better” and it doesn’t matter whether those students are Grand Prix riders or those with no intention of ever stepping into a show ring. She has a particular interest in helping young riders and often freely gives her time for educational programs aimed at young riders, especially if she can teach in-hand or long-line techniques, which she worries are being lost.

“All people are capable of hearing for that balance, but if I can teach them to follow the drum beat of the cadence, I can get them closer to following the rhythm. Tension, anger, etc. can block people from hearing and feeling,” she said.

Bettina Drummond – Working to Preserve the Art of Riding

When she reflects upon the state of riding education in America today, Drummond is not shy about admitting that she has great concern for the future of riding as art rather than sport. While vast amounts of money seem available for educational programs aimed at competitive riders, Drummond said there is little that is aimed at supporting riders as artists. And yet, she believes that is the very essence of classicism.

“I believe some process must be developed that gives young riders a moment to breathe, meaning that they are provided with the opportunity to think without worrying about financial survival,” she said. “As a youngster, I was lucky to be formed by some of the best riders. It was a tremendous experience. Today, too many young riders are sent to Europe to show and win, but not really train. What I would like to see, 30 years from now, is a true center of learning in the U.S. that allows people to study the ‘craft’ of riding and training. I am forever surprised at how much money is poured into dressage in this country and yet, none focuses on creating a true center for the study of riding theory. One cannot train from A to Z in gaps.”

Some years ago, one of Drummond’s mentors – Gen. Pierre Durand, a former head of the French National Equestrian School in Saumur – was asked his view on the question of whether dressage is art or sport. His answer was simply that “a true artist cannot imagine competition. It should be art first, then competition.”

Drummond is a complex person, but then, she is an artist and art itself is complex. Riding may be one of the most complex arts of all. This complexity may explain why so many search for that simple method that, if followed correctly, will make them great riders. But as Gen. Durand once said, one cannot ride by numbers and be a great, artistic rider any more than one can paint by numbers and become a great painter.

Drummond clearly doesn’t ride by the numbers. She rides to create her own version of art and hopes that in the end, it inspires others to follow their own artistic paths.

Poetry by Bettina Drummond

Early morning frost

Shadows weave across the light, a strange mosaic gift that stains my floor:

it takes my feet straying on to empty places. I walk within this narrow corridor

to find the years have fled my steps to whisper hints of truth within my heart.

They lie in dormant places creeping into form at times, in a breath or set apart.

The cold has found its voice, claims that all life now exists bleached to white…

All fails but naught cries out, the thwarted ice strikes sparks into a winter’s night.

The stallion in the garden

When halfmoon sets and satiated night retires,

when amongst the shadows sing unearthly choirs,

then the owl’s beat is measured out,

then the gleaming eyes are put to rout.

A fleeting glimpse of fire on silvered snow,

A fluid line of power in a constant flow:

from haughty neck steams measured pride,

from silent hoof streams in souls’ tide.

To catch the ember and fan its glow,

to spend the love and rue its part…

a stallion’s breath in winter’s throe:

a silent plea through a woman’s heart.